Publishers will lose out if generative AI becomes another duopoly

Earlier this month, Google quietly announced that its Gemini chatbot (now described as an ‘AI Assistant’) would have access to a user’s search history in order that it can provide more tailored responses. This follows the launch (and enhancement) of ChatGPT’s memory functionality. Similarly, this allows it to provide personalised responses to prompts based on previous interactions.

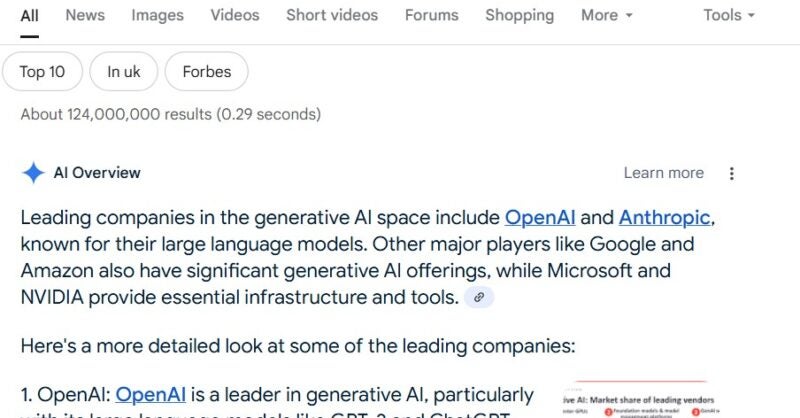

These product developments are attempts to address the central business problem facing AI labs: how to create defensible high-margin revenue (of the kind that large technology businesses are used to) when the foundation models which power these tools are trending towards commodity pricing. This became starkly apparent in the wake of the release of DeepSeek’s R1 model which performs at levels comparable to OpenAI’s top LLMs (large language models), but was trained (and can be operated) at a fraction of the cost.

Separately, Google this week moved closed to making generative AI the default option for search as Google AI-mode was made available to all users in the US.

Personalisation, and repositioning these consumer AI tools as all-purpose assistants rather than simply chatbots, tackles this challenge in two ways.

First, by increasing utility. AI responses are likely to be better when they are based on information about the user: if I ask for a restaurant recommendation for dinner with a friend tonight, the response will be more useful if it knows my dining companion is vegan.

Secondly, because they create switching costs. These are the costs incurred by consumers, either perceived or real, when moving between providers. They have the effect of cementing the position of a vendor, giving them pricing power and allowing them to extract more value from a customer than the market would normally tolerate.

Google and OpenAI’s recent updates to Gemini and ChatGPT are intended to drive up these costs.

As I use an assistant more and more, over time it will build up ever more data on my preferences, making it harder and less appealing to change. This process will be accelerated when these tools can use data from other applications; perhaps from your calendar, your email or your private messages.

Consider the analogy of non-AI assistants. Executives keep the same PAs for years – sometimes decades – because they understand how the exec wants to work, what they think of person X, their favourite restaurants, their partner’s birthday etc.

To give an example of how switching costs work in practice, consider the Android and iOS mobile ecosystems. Because of lost app purchases, integrations with other hardware and the need to learn and configure a new interface, consumers rarely switch between these ecosystems. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) found that, among recent phone buyers, just 8% of iOS users had switched from Android and 5% vice versa.

If high switching costs are successfully introduced into the AI market, that will cement the position of a small number of dominant businesses. Today’s general-purpose AI market is highly concentrated: four applications account for around 95% of the market.

This combination of concentration and lock-in is hugely troubling for the media.

As publishers, we cannot hold back the rise of this technology. Our businesses will have to adapt. Licensing looks set to become a critical source of revenue, sitting alongside the subscription and advertising income streams built around our owned-and-operated platforms (which will need to be laser-focused on content and experiences that cannot be substituted by an AI output).

As licensors of content to these AI applications, we want there to be healthy competition amongst them; both for users and for original, quality journalism that makes these tools more useful. This kind of vibrant, innovative market is how we secure fair payment for the value we bring.

The alternative world that Google and OpenAI are trying to create is one in which monopolistic tech firms can set take-it-or-leave-it terms; the same market dynamics that have plagued news media in the eras of search and social, which are dominated by the duopoly of Google and Meta.

What can be done about it?

Competition authorities should be looking at interventions now, as these markets are still developing and before it’s too late to prevent the negative outcomes described from coming to pass. The simplest solution is to ensure personal data is easily portable between AI systems. This would have the effect of dramatically reducing switching costs, ensuring AI applications would have to compete on their merits and increasing the incentives for innovation and new market entrants.

There are many analogous examples where regulatory action has driven down switching costs, to the benefit of consumers and businesses. Take the Open Banking regulations that made it easy to switch current accounts, leading directly to the recent wave of consumer fintech innovators like Monzo and Revolut. Or, further back, mobile telephone number portability which, by reducing switching costs, drove down mobile phone costs for consumers markedly.

The shape of the market for AI assistants – and the content and data to power them – is still up for grabs. Early action can ensure this is configured to serve consumers and creators, not just the interests of big tech.

The post Publishers will lose out if generative AI becomes another duopoly appeared first on Press Gazette.